Back in 2009, I began putting together a list of people to interview for my book, The Nashville Musician’s Survival Guide, and my friend, Mike was at the top of this list. Those of you who knew Mike know that he was a very caring, giving, and humble human being. The interview he gave was not only insightful for aspiring musicians, but also a wonderful insight into his musical journey. Although he has now gone on to a better place, his music can still be heard, and his magical essence still shines through the words on these pages. It is with that spirit that I’d like to share his words with you all. Mike touched so many lives, and we are all the better for it. I miss my friend.

Use the buttons at the top or bottom of each page to move to the next page; the full interview is around 10 pages long.

Whether you are a longtime veteran of your local music scene, a recent music school graduate, a hired gun working for a national act, or an aspiring independent artist, you all have something in common – that being a life centered around music. This life of music will lead you into many different performance situations. Like many of my musician friends, I have found myself in a plethora of musical situations over the years; including top 40 bands, rock bands, blues bands, national acts, and start-up original projects, to name a few. I’ve played at festivals, mud bogs, weddings, frat parties, blues jams, jazz jams, open mics, on the Grand Ole Opry, and of course, in nightclubs and bars, the latter being be the arena in which I have probably performed the most.

If there’s one thing I have learned over the years, it’s that you can never have a big enough repertoire. Back in my Berklee days, one of my guitars instructors once told me “You should start building your repertoire of standards. Not only will it help you find your musical voice, it will come in handy down the road”. Twenty-something years and thousands of gigs later, I’ve really come to understand the scope and importance of his words.

Unless you play nothing but your own original music, most live music situations will involve playing a night of cover material, and in my mind, this is a noble cause. The audiences of your typical local bar are usually folks that want to hear some “feel-good music” – familiar, often danceable party tunes that will help them forget about life’s hardships. Before the world had ever heard of “The Beatles”, they were a working cover band, as was Aerosmith, Huey Lewis, and many others.

By the time I entered my nightclub performance years in the late 80s, there was already a few decades of recorded popular music to pick from. Some consider this time period (50s through the 70s) to be the golden era of recorded music. This era gave birth to many songs that are still big crowd-pleasers, those certain tunes that always have a positive impact, no matter what the demographic. While the following decades would add more songs to this pool, it seems that the golden era provides the bulk of what we consider “classic hits” and standards. Over the years, many people have put together lists of the most covered songs, the most popular songs, the greatest hits of all time, etc. In 2004, Rolling Stone Magazine released a list of “500 Greatest Songs of All Time”. Upon scrolling through this list I saw many songs that I had played in different bands and situations over the years.

After cross-referencing that list with the song lists of several modern day cover bands, and comparing that with my own personal experiences, I have come up with a list of what I consider to be songs that every working musician should know. This list is by no means definitive or official; it’s simply my take on the most commonly requested classics, songs that many cover bands have in common, and songs that are often played when guest musicians sit in. Many of these songs are thoroughly worn out and greatly overplayed. Some might argue that many of these tunes have been beaten to death, while others might call this list “Dead Songs That Kill Bands”. Nevertheless, if you are planning on a lifetime of musical performance, knowing these songs, at the absolute least, will come in handy at some point.

| Aint no Sunshine | Bill Withers |

| Ain’t Too Proud to Beg | The Temptations |

| All along the Watchtower | Jimi Hendrix |

| All Right Now | Free |

| Blue Moon Of Kentucky | Patsy Cline |

| Born to Be Wild | Steppenwolf |

| Breakdowm | Tom Petty |

| Brick House | The Commodores |

| Broken Wing | Martina McBride |

| Brown Eyed Girl | Van Morrison |

| Can’t Get Enough | Bad Company |

| Crazy | Patsy Cline |

| Crossroads | Cream |

| Drift Away | Dobi Gray |

| Feelin Allright | Joe Cocker |

| Folsom Prison Blues | Johnny Cash |

| Free Bird | Lynyrd Skynyrd |

| Friends in Low Places | Garth Brooks |

| Georgia | Ray Charles |

| Gimme Three Steps | Lynyrd Skynyrd |

| Good Hearted Woman | Waylon Jennings |

| Hard to Handle | Black Crows |

| He Stopped Loving Her Today | George Jones |

| Hit Me With Your Best Shot | Pat Benatar |

| Honky Tonk Woman | Rolling Stones |

| I Feel Good | James Brown |

| Johnny B Good | Chuck Berry |

| Knock on Wood | Eddie Floyd |

| Knockin on Heavens Door | Bob Dylan |

| Last Chance For Mary Jane | Tom Petty |

| Little Sister | Elvis Presley |

| Long Train Runnin’ | Doobie Brothers |

| Mama Don’t Let Your Babies | Waylon Jennings |

| Margaritaville | Jimmy Buffet |

| Me and Bobby McGee | Janis Joplin |

| Mony Mony | Tommy James & the Shondells |

| Mustang Sally | Wilson Pickett |

| Old Time Rock and Roll | Bob Seger |

| Piece of My Heart | Janis Joplin |

| Pink Houses | John Mellencamp |

| Play That Funky Music | Wild Cherry |

| Pride and Joy | Stevie Ray Vaughn |

| Red House | Jimi Hendrix |

| Redneck Girl | Gretchen Wilson |

| Respect | Aretha Franklin |

| Roadhouse Blues | The Doors |

| Rock ‘n Roll | Led Zeppelin |

| Satisfaction | Rolling Stones |

| Save a Horse Ride a Cowboy | Big and Rich |

| Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay | Otis Redding |

| Some Kind of Wonderful | Grand Funk Railroad |

| Soulman | Sam and Dave |

| Stand by Your Man | Tammy Wynette |

| Standin On Shaky Ground | Delbert Mcclinton |

| Statesboro Blues | Allman Brothers |

| Stormy Monday | Allman Brothers |

| Summertime | Billy Holiday |

| Superstition | Stevie Wonder |

| Sweet Home Alabama | Lynyrd Skynyrd |

| The Chair | George Strait |

| The Joker | Steve Miller |

| The Thrill Is Gone | BB King |

| Tush | ZZ Top |

| Twist and Shout | The Beatles |

| Walkin’ After Midnight | Patsy Cline |

| What I Like About You | The Romantics |

| Wonderful Tonight | Eric Clapton |

| Workin’ Man Blues | Merle Haggard |

| You Really Got Me | The Kinks |

| You Shook Me All Night Long | ACDC |

Here are a few of what I consider to be the benefits of having a big repertoire of standards:

Requests. If you ever wind up playing some cover gigs, which many musicians do at some point, “standards” will often get requested, and you might find your band “winging” these songs to please audience members. This even happens with national acts.

Sitting in. Having a big repertoire of standards will give you some common ground when sitting in with a band. Back in my New England nightclub days, when friends would sit in with my bands, we would play standards. The same was true when I would sit in with their bands. In Nashville today, sitting in is one of the best ways to build your reputation as a player. Even when superstars sit in, it seems they often choose classic hits or standards over their own material.

Big Tips. If you already play in a cover band, knowing the most popular classics can help you earn some extra tips. I can’t think of how many times someone has said “I’ll give you guys $20 if you play Sweet Home Alabama again.” (Make it an even $50, and it’s a done deal!)

Song Structure. These songs were hits for a reason, and it’s not a coincidence that people still like to hear these songs decades after they were released. Whether it is your desire to be a great performer or a songwriter, internalizing some of these classic hits will teach you song form and structure, and give you perspective about what strikes a chord with the masses.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this list. Are there some songs you feel I missed? Are there songs on here that you think don’t belong? Wherever your musical path might lead, always do your best to smile when playing Mustang Sally, and never accept less than a $20 to play Free Bird!

Have you ever experienced hand or arm pain, or pain in your joints when playing a musical instrument? Perhaps you experience this pain while working at a computer or a mixing console? How about weakness or numbness in your hands or fingers? If you have, or do experience any of these symptoms on a regular basis you are not alone, you, like me, are one of many who live with repetitive motion injuries.

Several years ago, while working on the Toby Keith tour, I was helping the crew load some heavy cases onto a truck. Everything was going fine until one particularly hard-to-maneuver case began to fall off the ramp, with my hand still holding one of the handles. The case didn’t fall completely off the ramp and we were able to pull it back up, but not without my right elbow becoming engulfed in pain. My first thought was that maybe I had sprained something, but I had sprained joints before and they didn’t feel like this. This pain seemed to be centered on my right elbow, and was an intense, burning sensation, like my elbow was on fire. I also felt pain if I squeezed or gripped anything in my right hand. I was instructed by the road manager to get it checked out by a doctor as soon as we returned to Nashville.

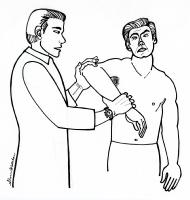

At the time of this incident I had already been playing guitar for over 20 years, I had previously worked in construction for several years, and was currently performing a fairly physical job as a guitar tech. All of those years of daily, repetitive hand and arm motions suddenly caught up with me, hurling me full speed into the world of “repetitive motion injuries”. According to the doctors, I had developed tendinitis, and while this incident with the road case may have acted as a trigger, “it had likely been a long time in the making”, they explained. “So how do we heal this?” I asked.

The approach that the doctors chose for me was a regular course of anti-inflammatories, a steroid shot, an arm brace, and the recommendation to “do your best to avoid lifting or gripping anything heavy”, the last piece of advice being somewhat unrealistic for a guitar tech. Although I did follow these recommendations, even adapting some of the physical elements of my job, several weeks later I was still experiencing a lot of pain on a daily basis. It still hurt to grip things with my right hand, and I was beginning to have wrist pain and numbness down my arm. With my situation worsening, the doctors now recommended physical therapy, and this is where I finally began to see some results.

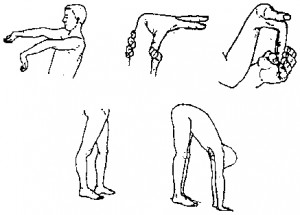

The physical therapist took an entirely different approach. He showed me several hand and arm stretches, which I was instructed to perform daily, he massaged the area of inflammation, and iced it. He showed me how to do the massages myself, and instructed me to do them every morning and night after the stretches, the application of ice always being at the end of the routine. He told me to “listen to my body” and that to perform my regular physical activities as long as they didn’t cause pain. “If an action begins to cause pain, try not to do it.” Making great improvements over the following weeks, I couldn’t understand why the doctors hadn’t recommended any of these approaches. In fact, the doctors did very little to explain the finer points of my affliction, most of what I learned about what causes tendinitis and how to deal with it, I learned from the physical therapist.

The physical therapist took an entirely different approach. He showed me several hand and arm stretches, which I was instructed to perform daily, he massaged the area of inflammation, and iced it. He showed me how to do the massages myself, and instructed me to do them every morning and night after the stretches, the application of ice always being at the end of the routine. He told me to “listen to my body” and that to perform my regular physical activities as long as they didn’t cause pain. “If an action begins to cause pain, try not to do it.” Making great improvements over the following weeks, I couldn’t understand why the doctors hadn’t recommended any of these approaches. In fact, the doctors did very little to explain the finer points of my affliction, most of what I learned about what causes tendinitis and how to deal with it, I learned from the physical therapist.

Over the following months I was able to get an upper hand on my tendinitis, and through regular stretching, didn’t have any more problems for several years. Then I had a setback. One day I was making a homemade pedal board and spent several hours tightly gripping and squeezing a rivet gun. The end result was a resurgence of the pain in my right elbow as intense as that caused by the Toby Keith road case incident. I paid a couple more visits to a physical therapist who was able to help with some soft tissue manipulation, but the biggest thing he did to help me long term was to introduce me to a whole new way of stretching. The following, which I quoted from my book “The Nashville Musicians Survival Guide”, is part of what I learned.

“The muscles in your arms are actually a series of overlapping interconnected muscles, tendons, and ligaments that run from your fingers all the way to your shoulder. It is because of this fact that it is important to also stretch areas of the arm that might not have any pain or problems. Performing stretches that work your wrists, triceps, and shoulders will ultimately help stretch all the muscles and tendons in between.

Stretching an arm with tendinitis is not the same as stretching a healthy arm and requires some caution. Listen to your body. The stretching should cause some sensation but should not be painful. The more you stretch, the more results you will experience. Stretch at regular intervals throughout the day, always making it a point to warm up with some light cardio before your first stretching sequence. (Stretching cold muscles can cause further injury.) If you are gigging, try to stretch before the performance, after the performance, and even in between songs if you have a chance”…

Taken a step further, it only makes sense to stretch and exercise your entire body, as everything is truly connected… the hip bone’s connected to the leg bone, the leg bone’s connected to the…

I was able to eventually get my recent tendinitis flare up under control, but this affliction still haunts me to this day, with a constant effort required to keep it at bay. If I don’t stretch regularly, the pain comes back, and as the body ages it seems like we are more predisposed to injury – gravity is not on our side. That being said, something that has helped me greatly has been an investment in overall physical fitness, health and well-being. I’ve tried a lot of different exercise programs in recent years, my favorite being the “P90X series” of which I have done several rounds. But I must say that yoga seems to be the one exercise that has helped my overall situation the most, it’s absolutely outstanding for overall flexibility.

Eating healthy food doesn’t hurt either. In fact, there are certain foods that increase inflammation, and others that help to decrease inflammation.

Foods that help decrease inflammation:

Foods containing Omega-3 fatty acids like cold water fish, canola oil, and pumpkin seeds; Olive oil, nuts, fruits, vegetables, lean poultry, legumes, tofu, ginger, and some herbal teas

Foods to Avoid

Junk foods, high-fat meats, sugar, and highly processed foods are at the top of this list. Avoid anything that contains high amounts of trans fats and saturated fats like red meat and high-fat processed meats such as bacon and sausage.

For more info on what foods to eat or avoid, follow this link to read the article from which much of this nutritional information was taken, or visit the website, Do It the Hard Way, to learn some nutrition basics and find healthy recipes.

Unfortunately, we live in a society that tends to address problems only as they occur, rather than focusing on prevention. When I think back to all my years of guitar lessons, even my years of music college, no instructor ever told me that repetitive motion injuries exist, let alone how to prevent or deal with them. If you’re a musician and don’t yet have any of these afflictions, it’s obvious that physical fitness and overall health and well-being will reduce your chances of ever having these problems. And if you are “playing with pain”, you’re not alone, there are many of us. But the good news is that most problems are treatable, there are solutions – they just require a little knowledge, a consistent effort, and some self-investment.

“Every human being is the author of his own health or disease.”

— the Buddha

To gain some more perspective on repetitive motion injuries, as well as some of their common misconceptions, follow this link and read “A Cure for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome?” by Jennie Hoeft, as it was reposted on Nashville drummer, Stephen Taylor’s blog.

I’ve wanted to take a step with my vocal abilities for some time now and this year seemed like a good time to do it. A few months ago I dug out an old vocal method book, “The Rock ‘n Roll Singer’s Survival Guide” by Mark Baxter, a vocal coach I had studied with in Boston in the late 90s. After digging into it for a few weeks I came across one of the books many great recommendations – the importance of taking voice lessons from a vocal coach – and that was all I needed for encouragement.

I had recently heard some great things about Nashville-based vocal coach, Judy Rodman, so I decided to give her a try. In early March I took my first lesson at her home studio, a one hour session during which we covered a lot of ground. After discussing my current musical activities and goals, she began the lesson by demonstrating some “mechanics” about the human voice, partially aided by the use of models and diagrams. Then she took me through some warm-ups, all the while listening and observing my “habits.” Next, she had me sing a song of my choosing, and this is when it became even more apparent that she had a truly unique approach to vocal training.

After strapping on my guitar, she had me sing into a mic that was plugged into a couple of floor monitors to emulate a live gig. I don’t think I sang more than a verse before she told me to stop so she could address some issues. Apparently, years of guitar playing, combined with other “intellectual pursuits” had allowed me to develop some bad posture, posture that was restricting my vocal abilities. To begin correcting this, she had me sing while standing with my head and one heal up against the wall, while allowing my shoulders and back to be loose.

She also introduced some other concepts to improve my vocal “path.” One I found particularly enlightening was to pick an object or spot on the wall and imagine that it’s a person to whom I am telling a story. Another was to pretend I’m singing to a deaf person, to cause a deeper articulation of the words and phrases. Yet still another was to raise my eyebrows when I sing, as this expands “the cave” and will allow for a more resonant sound. By the time I left the lesson I was not only inspired to go home and practice, I had made an immediate and noticeable improvement.

Since that day I’ve taken a half-hour lesson every other week and have made great strides, and I actually look forward to practicing! Like any great music teacher or coach, Judy has a gift for custom tailoring each student’s approach and practice regimen; she quickly honed in on my problems and came up with the appropriate exercises and concepts to correct them, each lesson introducing new ones. If you live in middle Tennessee (or anywhere for that matter, as Judy also gives lessons over the phone or via Skype), and are in need of some vocal coaching, I highly recommend Judy, she is truly a vocal coach extraordinaire!

Well that’s it for today; it’s time to go sing!

“Teaching is the profession that teaches all the other professions.” – Author Unknown

When I first arrived in Nashville in 2002, I realized that to succeed in this massive and confusing music industry I would be faced with great challenges in the months and years ahead. I was fortunate, however, as I had a good friend in the industry – one who had already paid his dues and found some success here, and he helped to illuminate a path that worked for me. He was my Nashville mentor.

“You may be only one person in this world, but to one person at one time, you are the world.” – Anonymous

He didn’t consider himself a Mentor, or teacher, he was simply a good friend helping another friend. But I was clueless about how this music industry worked, so to me he was a lifeline of information and inspiration. He knew I needed this guidance and direction, and for whatever reason, he decided to invest in my future. He went out of his way to help me on many occasions – advice-filled phone calls, one-on-one guitar lessons, trips to the music store to check out new gear, introductions to friends in the business, he even gave me an electric guitar.

“The dream begins with a teacher who believes in you, who tugs and pushes and leads you to the next plateau, sometimes poking you with a sharp stick called ‘truth.’ “- Dan Rather

What he offered that probably helped me the most was insight and advice. He had already been working in this town for 10 years at this point in time, so he had a great perspective of a much larger view of the music community than one could see quickly. His accumulated wisdom also allowed him to see my strengths and weaknesses. After one embarrassing moment in a Nashville nightclub, one where I sat in and played a style in which I was in over my head, he was compassionate, but brutally honest.

“You might want to stay away from downtown for a little while; you need some more wood shedding.”

As much as I didn’t want to hear this, I knew it was the truth and I knew that there was more work to be done. Over time, I improved my weaknesses, largely thanks to his advice and suggestions, and returned to the in-town nightclub scene better prepared. I eventually wound up playing as a sideman on tours, recording on songwriter demos, etc. and I have been fortunate to wind up in the category of musicians who find a way to survive Nashville. If it weren’t for the great help I was given early on by this generous human being, who knows how it all would have turned out.

“A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops.” – Henry Brooks Adams

Years before I moved to Nashville I was a guitar teacher in New England. I taught 30 to 40 students privately per week. I did my best to help all of them, but some were more receptive than others, and for many my teaching went beyond the half-hour lesson – helping them pick out instruments, inviting them to sit in with my band, phone conversations – I gave more than I was expected to because it felt like the right thing to do.

Now, 10 years later, I have learned that one of these students is a guitar teacher himself and plays in a successful nightclub band as well. Another one of these students that received some extra “mentoring” went on to graduate from the Berklee College of Music and is earning his living as a touring musician. And still another former student, one who earns his living in the corporate world, continues to enjoy the healing power of music in his private life.

“There are two way to live your life. One as though nothing is a miracle, the other as though everything is a miracle.” – Albert Einstein

I too believe that life is a miracle and shouldn’t be taken for granted. Long before I had my Nashville mentoring, there were several other “mentor-like” figures in my life. These people acted in a selfless way, reserving judgment, and accepting me as I was, while doing many great things to help me become a better person. My wife, Kelly is one of these great people. To this day, she continues to help me shape my life in a way that makes me better, while still accepting me for who I am.

At this point of my life I am glad to be in a position where I can help some others along the way. For many, the Nashville dream is a tough row to hoe, and the book I just wrote is designed to help some of these struggling folks – kind of my way of paying it forward. And when someone asks me for advice I always do my best to offer insight that will really help that person.

So I urge you to take a minute and ask yourself a couple of questions – Who in your life is looking to you for answers? How can you help them on their path? If you put your best foot forward and help a few folks along the way, if nothing else, you’ll sleep better at night knowing that you did your small part to make the world a better place.

“Together we can change the world, one good deed at a time.” – Pay it Forwarders everywhere

As some of you may know, and for those of you who don’t know, I have just released my book “The Nashville Musician’s Survival Guide.” This street-level perspective of the music-related jobs in the Nashville music industry is now available in print and eBook versions. To purchase your own copy, follow this link.

Are you ever in complete silence? During the quietest moments of your life, lying in bed about to fall asleep or sitting alone in a quiet room, can you hear the sound of nothing? I wish I could say I can but I can’t. My ears ring constantly, every second of every day, and it’s been that way for over 10 years now. I have permanent nerve damage in my ears from the result of playing music too loudly for extended periods of time without ear protection. I have tinnitus.

“Tinnitus” is derived from the Latin word tinnire, which means to ring. As stated in Wikipedia, it can be caused by a variety of situations; ranging from exposure to excessive sound pressure levels for extended periods of time, ear infections, foreign objects in the ear, nose allergies that prevent or reduce fluid drain, or wax buildup. But sounds at excessive volume seem to be the most common cause. It is an extremely common condition, affecting as many as 50 million Americans (of which about 12 million have it severe enough to seek medical attention). And sadly, it is a condition for which there is no cure.

“You´re head is humming and it won´t go in case you don´t know…” – Robert Plant – Stairway to Heaven

That’s right, once you have it you will always have it, and it can progress if preventative measures (they’re called earplugs) aren’t taken.

“I have severe hearing damage. It’s manifested itself as tinnitus, ringing in the ears at frequencies that I play guitar. It hurts, it’s painful, and it’s frustrating.” says Pete Townshend. The excessive volume of The Who’s live performances combined with the deafening volume in which he (and John Entwhistle) listened to playbacks through studio headphones has resulted in tinnitus so severe that some reports have said he can’t even hear his phone ring. His affliction with tinnitus has caused him to abandon electric music performance more than once in recent years, rendering it only practical to play acoustic music live, as has also been the case with artists like Neil Young and Bob Dylan.

It’s not just caused by loud music either. It can be caused by any regular prolonged exposure to excessive volume. For instance, many members of our armed forces are exposed to everything from explosions to jet engines and gunfire to loud machinery, one recent article in the New Yorker estimating it affects nearly half the soldiers exposed to blasts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

How much volume can your ears handle?

How many times have you walked into a venue in which a band was playing and thought it was too loud? The human ear was simply not meant to withstand the sound pressure levels produced by megawatt PA systems, electric guitar amps, and even the acoustic, unamplified drum kit in close proximity (especially when played with some conviction). The following chart from the OSHA website shows what is considered permissible noise exposures:

|

Duration per day, in hours |

Sound level in dB* – Decibel level |

|

8 |

90 |

|

6 |

92 |

|

4 |

95 |

|

3 |

97 |

|

2 |

100 |

|

1.5 |

102 |

|

1 |

105 |

|

0.5 |

110 |

|

0.25 or less |

115 |

Your ears can be exposed to sound pressure levels of 90 dB for eight hours, after which point hearing damage can occur. This ratio is a sliding scale, so when the decibels are increased to 110 decibels (the volume of an average rock band), hearing damage can begin to occur in 30 minutes. The louder the SPLs become (sound pressure levels) the less duration your ears can handle.

Decibel Levels of Environmental Sounds (also from the OSHA website)

|

Source–Dangerous Level |

dBA SPL |

|

Produces Pain |

120-140 |

|

Jet Aircraft During Takeoff (at 20 meters) |

130 |

|

Snowmobile |

120 |

|

Rock Concert |

110 |

|

Die Forging Hammer |

100-105 |

|

Home Lawn Mowers |

95 to 100 dB |

|

Semi-trailers (at 20 meters) |

90 |

|

Source– |

dBA SPL |

|

Discomfort Level |

Above 80 |

|

Heavy Traffic |

80 |

|

Automobile (at 20 meters) |

70 |

|

Vacuum Cleaner |

65 |

|

Conversational Speech (at 1 meter) |

60 |

|

Quiet Business Office |

50 |

|

Residential Area at Night |

40 |

|

Whisper, Rustle of Leaves |

20 |

|

Rustle of Leaves |

10 |

|

Threshold of Audibility |

0 |

A friend of mine who lives in New England, one of my former guitar students, recently told me his ears have been ringing for about two years now. He plays in a popular regional jam band on the rise, Superfrog, a spirited group of young players making their mark across the Northeast. As did I in my earlier New England gigging days, they play with an energetic reckless abandon, and they, along with their loyal followers, are living in the magical moments of some of those roaring nightclub dance parties. When he first told me of the recent development of his tinnitus I don’t think he realized the true nature of this beast, how it can slowly progress over many years until it reaches the near unmanageable level of the Pete Townshend’s of the world. Upon discussing it with me he has now decided to invest in some custom musicians ear plugs, with his fellow bandmates also following suit. Some of the other guys in his band don’t have tinnitus yet, and adopting earplugs into their world may ensure they never do.

Living with Tinnitus

“Yes, it’s in my left ear. It’s excruciating…I mean, it’s the worst thing ’cause it’s not…It never…It does go away – it’s not true to say that it doesn’t but, uhh…It doesn’t…The doctors say it won’t…It isn’t actually going away – you’ve just gotta suppress…They try to come to terms with what it actually… Why some people fear it – that’s the psychology behind it. They know it’s there but why is it such a horrible sound? Well, you can say why is a guy scratching at a window with his nails such a horrible sound – I couldn’t put up with that! This is worse!” – Jeff Beck from an MTV interview in June 1993

The thing about tinnitus, and perhaps one of the reasons it’s hard to detect in its earliest stages, is that you don’t notice the ringing all the time, even though it’s always there. It depends on the threshold of the sound around you. If you are on the go from the moment you wake up till the moment you lay down to go to sleep at night, you likely won’t hear the ringing throughout your day, as many of the sounds of everyday life will mask it. It’s the quietest moments when it chooses to show itself. The concept of “masking” is quite useful, if not essential, for many tinnitus sufferers. I have a noise generator beside my bed that plays sounds of the ocean while I sleep. I set it on a volume that is just above the volume of my ringing, and this masks the ring enough for me to fall asleep. Some severely afflicted tinnitus sufferers use portable noise generators or play MP3s of soft music or different types of noise for most of their day, all in an effort to mask the relentless sounds in their head.

Some findings might suggest that avoiding or cutting back on alcohol, caffeine, and salt, among other substances, can help reduce the ringing. As tinnitus is considered partly a subjective condition, it becomes difficult to gauge how different variables affect the level of the ringing. I can’t say that I have personally had any success by adding or omitting any parts of my diet.

Stopping It Cold In Its Tracks

“Later in the evening as you lie awake in bed, with the echo from the amplifiers ringing in your head.”

– Bob Seger – Turn the Page

You can’t get rid of it but you can stop its progression. The one thing that has become completely obvious to me is that earplugs during exposure to loud sounds are ABSOLUTELY ESSENTIAL to prevent the ringing from escalating. I have been wearing custom molded musician’s earplugs, which can be acquired for about $150 with a visit to your local audiologist, for about 12 years now. I wear them not only when performing live with a band, but when mowing the lawn, vacuuming, operating a power saw, anything that causes excessive SPLs. When I’m sleeping on a tour bus, I sleep with foam earplugs to cut down on the rumble of the road. If I fly, I wear earplugs the whole time on the plane.

I’ve also learned how to turn down my music a bit. I’ve experimented with using less powerful guitar amps, speaker attenuators, and drummers that don’t “bash” quite so much. I’m cautious when recording with headphones as well, watching the volume and taking breaks often.

I urge everyone to heed this message. If you play loud music regularly, either live or in the studio, consider the earplugs option, it will be the best $150 you’ll ever spend on gear. And think about your audience too. Are you blowing them out of the room with your guitar amp, lead vocal, or snare drum? Is your band louder than it needs to be to get its point across? Are your ears ringing regularly from your construction job or your job at the airport? Are your kids listening to iPods on 11 all day long? If you think the answer might be yes to any of these, don’t wait until it’s too late to become proactive. Act now or you might wind up hearing the sound of a continual dog whistle for the rest of your life.

So when you have a quiet moment, ask yourself, your family, and your friends this one simple question –

Do you ever hear the sound of true silence?

When I was 12 years old I was inspired to learn how to play the guitar after hearing the music of Jimi Hendrix. As I began learning, I quickly realized I would have to put a lot of effort into this endeavor to be able to make the kind of music that Jimi inspired me to make. So I dug in, and the more I dug in and applied myself, the better I became at my craft. As I got better, it started to become more fun too. Early on I made the connection that the more I applied myself (by practicing, wood shedding, experimenting, etc.) the more I enjoyed guitar playing. For me, practicing my guitar, and enjoying the act of guitar playing go hand-in-hand, and I never viewed practicing as a chore I had to do.

As the years churned on I never stopped applying myself. I eventually went to Berklee, began playing professionally, and still work at improving and honing my skills 20 years later (even though I can maintain a decent level of proficiency without doing so). While some people along the way have suggested that I practice more than I need to, I disagree. Putting in such a big effort over a long period of time has not only made me a better musician, it’s made me a better person. It’s benefited my life in ways that go way beyond music. If you can teach yourself self-discipline through the mastery of your craft, you will forever have an increased self-discipline in every facet of your life, more patience, problem-solving skills, the list goes on.

In my opinion, too many musicians coming up in the world today learn a bare minimum of proficiency early on and then just coast. So many are consumed by aspirations of fame and fortune that they miss out on the rewarding feeling one can get from just working towards being great at something. Whether you you play music as a career or just for fun, I believe that the more you put into developing your craft, the better your whole life will be. Practice might not make you perfect, but it will make you better.

Have you ever challenged yourself with something really, really hard. I mean something so difficult that initially you weren’t even sure if you could do it? Challenges like running a marathon or completing a triathlon, learning to speak a new language, losing 100 pounds, or mastering a musical instrument are all daunting tasks that can take months or years to accomplish and require an extreme level of “stick-to-it-ness”. Initially, this challenge might not be something that you need to do, but something that you want to do, or maybe even feel compelled to do. You take on this challenge simply to see if you can do it and because you sense it will make you a better person. The reward might be unknown at the onset and not come for a long time if ever, but still you march on with this challenge because it feels right.

Many years ago I was faced with such a challenge when I was playing guitar in the New England-based band “Crossfire”. The year was 1990 and the bands leader, Rob Gourley, suggested that I learn the Eric Johnson instrumental “Cliffs of Dover”, as he felt it might be a good showcase for me at our shows. He said that this was not something he expected me to do, but that if I wanted to learn it, the band would play it.

At this point of my life I had just finished my Berklee education, an extremely challenging experience in and of itself, so the idea of learning a four-minute piece of complex guitar music didn’t sound too daunting. At least that was my initial perception.

So I embarked on this new guitar journey. I outfitted a makeshift studio in an empty bedroom at my friend, Pete’s house with a practice amp, a boombox, a reel to reel tape deck, a metronome, and a music stand. I went out and purchased a copy of Eric Johnson’s “Ah Via Musicom” on CD as well as the guitar transcription and got to work. And work it was. When I had first heard this piece of guitar magic on the radio I recognized its brilliance, but Johnson’s impeccably fluid technique almost masks the songs difficulty. He made it sound easy, and easy was something I quickly discovered this song was not.

By the time I had put a couple of afternoons into it I realized this process was going to take weeks, maybe even months to be able to do the song justice, but that was no deterrent. I quickly realized if I could master this piece, not only would it be a great showcase for me with my band, it was going to make me a better guitar player in the process.

Crossfire was a steady working band and my only job at this point in my life, performing all over New England 3 to 4 nights a week. So my daily routine during this phase consisted of sleeping late, eating a late breakfast or early lunch, and then heading over to my “guitar studio” for an afternoon of extreme woodshedding.

I began with the intro and learned as much of the opening passage as I could by ear. When I came across a phrase I couldn’t interpret I used the sheet music. When things still didn’t make sense, I used the reel to reel tape deck to slow the song down to half speed. Gradually, one phrase at a time, it began coming together. After a couple of weeks of this I could make it halfway through the song, granted with many mistakes and not very smoothly. I labored on. After about five or six weeks I knew the entire song note for note but could still not play all of it at tempo. So I began practicing the most difficult passages at slower tempos, one phrase at a time, sometimes running a one bar phrase over and over for 10 or 15 minutes, gradually nudging up the tempo of the metronome. Of course a one bar phrase of Cliffs of Dover might be a flurry of 10 or 12 notes played in about a second.

Finally, after about three months of making my friends and family crazy, shredding my fingers to the bone, and a couple of ugly moments when I almost threw the guitar through a window, I was ready to present it to the band. We made a few passes one day during a sound check/rehearsal and we were good to go. The crowd loved it when we played it later that night, and it became a staple in our set for the next two years. My performance on this piece gradually improved over that period, as the experience of playing it live helped me to further kick it up a notch. The song was so difficult to execute that I still practiced it daily during this period. Eventually I left Crossfire for another band and although I continued to play this piece, it wasn’t long before I put it aside.

Looking back, Cliffs of Dover was the hardest piece of music I have ever learned. I probably put between 200 and 300 hours into it prior to ever playing it with the band. But I do remember feeling instant results after I could play it. Performing less technical songs and solos became easier. My hands and fingers were stronger and my stamina had improved. My ear had also improved making it forever easier to learn new pieces of music.

Lately I’ve been feeling the need to challenge my playing again so I decided to bring this piece out of the closet. I sat down with it a couple of weeks ago and have been working it back up to speed ever since. It’s been 15 years, and the process of sitting down with it again is like visiting an old friend. Although not as daunting for me as it was back in 1990, it’s still a bitch, and I have a ways to go yet. Once I can get it to a point I feel comfortable with, I’ll post a video for you all to check out.

Completing this challenge was hard back then, and it’s hard again right now. But I believe it is these kinds of challenges, self-imposed or other, and the new horizons they lead us to that encapsulate the best of the human spirit.

As a guitarist, having good control of vibrato has been a key component in my ability to effectively communicate through my  instrument. For many music purists, the use of vibrato has been widely debated, as so many artists and performers have used it with such a wide variance of efficiency and taste. There is the rapid fire, “billy goat” style vibrato as used by singers like Joan Baez and Eddie Vetter, the emotive, stinging vibrato used by guitarists like Jimi Hendrix and Buddy Guy, and the stark, subtle almost non-vibrato of Miles Davis. All these styles, and others, have their place, but some approaches, arguably, may be more effective than others.

instrument. For many music purists, the use of vibrato has been widely debated, as so many artists and performers have used it with such a wide variance of efficiency and taste. There is the rapid fire, “billy goat” style vibrato as used by singers like Joan Baez and Eddie Vetter, the emotive, stinging vibrato used by guitarists like Jimi Hendrix and Buddy Guy, and the stark, subtle almost non-vibrato of Miles Davis. All these styles, and others, have their place, but some approaches, arguably, may be more effective than others.

When I was first learning how to play guitar, it took all of my ability to simply play notes and chords cleanly, I wasn’t even aware of what vibrato was. A few years later, as I progressed, I gradually began to learn about the concept of vibrato from other guitarists. But my early development, similar to that of many guitarists, led to a quest for speed, rather than emotional content. When you are playing fast all the time, there is little time for vibrato as you never land on one note long enough to apply it. Fortunately, my early possession by a speed demon eventually came to an end, and a stronger, more pronounced sense of vibrato gradually became inherent to my playing.

What is vibrato? Here is a definition from the website answers.com:

“Vibrato is a musical effect consisting of a regular pulsating change of pitch. It is used to add expression to vocal and instrumental music. Vibrato can be characterized by the amount of pitch variation (“depth of vibrato”) and speed with which the pitch is varied (“speed of vibrato”).”

It goes on to say:

“The use of vibrato is intended to add warmth to a note. In the case of many string instruments the sound emitted is strongly directional, particularly at high frequencies, and the slight variations in pitch typical of vibrato playing can cause large changes in the directional patterns of the radiated sound. This can add a shimmer to the sound; with a well-made instrument it may also help a solo player to be heard more clearly when playing with a large orchestra. This directional effect is intended to interact with the room acoustics to add interest to the sound, in much the same way as an acoustic guitarist may swing the box around on a final sustain, or the rotating baffle of a Leslie speaker will spin the sound around the room.”

This brings up my first point, the battle to be heard. Although they are using classical music in the context of an orchestra, I believe the concept is universal. If you’re performing with a live amplified band, whether singing a lead vocal, playing a signature lick on a violin, or wailing a guitar solo, there is usually an effort required to make those notes audible and impactive above the roar of the band. Think of the total sound made by the band as one giant wall of sound. The lead melody, in most situations, is simply a group of chord tones and passing tones that fit into that wall of sound. A good strong melody in and of itself usually contains enough motion to create a contrast against the wall of sound, but when the melody sustains on a note, it begins to blend in. Using vibrato on those sustaining notes and at the end of phrases can create additional movement and allow the note to have a greater contrast against the otherwise static wall of sound upon which it sits.

This brings up my first point, the battle to be heard. Although they are using classical music in the context of an orchestra, I believe the concept is universal. If you’re performing with a live amplified band, whether singing a lead vocal, playing a signature lick on a violin, or wailing a guitar solo, there is usually an effort required to make those notes audible and impactive above the roar of the band. Think of the total sound made by the band as one giant wall of sound. The lead melody, in most situations, is simply a group of chord tones and passing tones that fit into that wall of sound. A good strong melody in and of itself usually contains enough motion to create a contrast against the wall of sound, but when the melody sustains on a note, it begins to blend in. Using vibrato on those sustaining notes and at the end of phrases can create additional movement and allow the note to have a greater contrast against the otherwise static wall of sound upon which it sits.

Leopold Mozart, father of the famous composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, wrote a textbook for violin instruction, Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule which was published in 1756. In it he writes “there are performers who tremble consistently on each note as if they had the permanent fever. ” Although he ultimately condemned the practice, he does go on to suggest that vibrato should only be used on sustained notes and at the end of phrases.

This is where the line between preference and taste becomes greatly blurred. Many successful artists use an excessive amount of vibrato, such as the previously mentioned vocalists, and this creates the trembling effect as noted by Mozart. And while this does not prevent these artists from having successful careers, this kind of “billy goat” style vibrato is often the result of a less than stellar technique. The lead melody was already designed to sit on top of the mix, containing enough inner motion to do so without constant vibrato. By singing with a constant vibrato, it’s like putting extra notes in where they weren’t intended. Some musicians and singers create these habits early on and simply choose to stick with what works for them.

Now take this to the other extreme. Listen to, or envision the sound of a great David Gilmour guitar solo. The fast passages are  played cleanly with no vibrato, but then at the end of the phrase, he might just sit on the last note for a few seconds before slowly and incrementally adding some substantial vibrato, usually at a speed that is a subdivision of the songs tempo. A lot of great blues and jazz musicians also employed this technique as well as vocalists like Etta James, Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra, and Paul Rogers.

played cleanly with no vibrato, but then at the end of the phrase, he might just sit on the last note for a few seconds before slowly and incrementally adding some substantial vibrato, usually at a speed that is a subdivision of the songs tempo. A lot of great blues and jazz musicians also employed this technique as well as vocalists like Etta James, Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra, and Paul Rogers.

This concept radiates my other point, our need to express. Music is simply communication. As a musician we are trying to convey or communicate stories, concepts, ideals, and emotions. Vibrato is simply one of the tools on our palate. So are dynamics, volume, speed, phrasings, etc. If you play constant 16th notes in your solos or drum fills, there is no contrast, the passages will be static and predictable. Insert some slower phrases within the fast flurries and the slow passages will create a contrast, ultimately giving more meaning to the 16th notes. I believe the same is true for vibrato. Use it constantly, and there is no contrast. Use it where it is most needed and most effective, and it will only serve to enhance your overall expressiveness.

From an electric guitarists standpoint, I like to use vibrato not only to create drama within a lead line, but also to help coax more sustain out of a note, and at times to induce controlled feedback. I’ve also adopted the technique of adding vibrato to the end of a bent note, a trick I learned from listening to recordings of guitarists like Jimi Hendrix and SRV. Of course, some would argue that true vibrato must come from a feeling, not a thought

This is all highly subjective and to be taken in stride. Explore the endless possibilities of vibrato but don’t overthink it, it should feel natural. Like one of my great instructors at Berklee once said “Practice your technique at home. But when you get to the gig, just play.”

Throughout my career as a professional guitarist I’ve played in all sorts of bands, and in all sorts of situations. I’ve played in rock bands, blues bands, jazz trio’s, and eight-piece country bands, and performed in night clubs, sports arenas, on flatbed trailers in a field, and at giant outdoor festivals. One of the biggest challenges of live performance has been the ongoing battle to achieve a palatable overall stage sound. As most musicians, myself included, use the same gear from one show to the next, this leaves the PA system, the sound engineer, and the natural  acoustic “space” of your performance as the variables that will regularly change.

acoustic “space” of your performance as the variables that will regularly change.

Let’s face it, most music performance venues are an afterthought. Whether it be a sports bar with a band in the corner, a tin roofed industrial building turned concert hall, or a 15,000 seat concrete sports arena moonlighting as a major concert venue, many of these situations simply don’t sound very inspiring. As a player in the band, I’m always trying to coax every ounce of sonic maximization out of every sound check or gig. But sometimes, no matter how much we keep tweaking monitor mixes, changing the angle or location of amplifiers, or notching annoying frequencies out of the PA, we just seem to wind up with a different version of mud. It is in these situations especially, that technique, concept, and style can have a huge bearing on the overall sound.

I saw an interview with Peter Frampton where he talked about a point early in his career when he transitioned from playing clubs and concert halls to sports arenas and stadiums. He mentioned how the sound was often less than great and that he adapted his songwriting style to work better in the context of “arena rock”. In the interview, he demonstrated this approach by playing a few simple power cords back to back and allowing the chords to ring openly. When I saw this interview, it not only reinforced a little of what I already knew, it got me thinking about how and  why this would make sense.

why this would make sense.

When sound is in an acoustic space that results in a loss of definition, some of the finite details of a musical performance become lost in the mud, often because of an overly exaggerated natural reverb and/or certain over accentuated frequencies. This is especially true in large cavernous buildings, or at over sized outdoor festivals. If you’ve ever played in these situations, you may have noticed that the ballads often tend to sound and feel better than the up-tempo songs. One of the reasons for this is because a slower tempo allows for longer note durations, and longer pauses, or more space, in between the notes. Playing in a larger physical space means that it takes longer for a note to develop and bounce off of a wall, and by playing long slow passages you are allowing these notes time to develop before bombarding them with the next note. You are playing into the inherently slow reaction time of a large or inefficient space and working with this handicap.

Now think of this phenomenon in reverse. You are playing a busy, up-tempo song in the same clumsy, nondescript acoustic environment. The bass player is playing a pedal of steady eighth notes on the low E, but because of the nature of the room, it just sounds like one big long note. The intricacies of the cymbal work seem to get lost, and the guitar solo doesn’t seem to cut through the mix. Needless to say, the vocalist is now having a difficult time singing over the roar. The room is just too loose to handle this many notes in rapid fire succession at a high volume, and turning the mix up or down doesn’t seem to help. When all else fails, simplify. Rather than just playing the exact pattern of the studio recording of a song, or your interpretation thereof, try adapting your part to fit the sonic inadequacies of a particular situation. Maybe quarter notes on the bass and a simpler pattern on the hi hat will help create a more open, and spacious mix. Perhaps simplifying the guitar part by leaving out certain rhythmic nuances that are getting lost anyway will create a better feel in the moment.

Back in the early 2000’s a friend of mine asked me to sub a gig for him on a national tour. His advice was to learn the material to the best of my abilities, but to play “big and spacey”. In the years since, I’ve worked hard at my ability to play into the sound of each “space” and have learned that not only is less more, quite often, less is better. Playing simply in live situations allows each note to have more meaning and also creates more space in the overall mix for the other instruments. And when all the players of a group work within this mindset it can also result in a more controlled, and often more inspired stage sound. So if you’re playing a show and it doesn’t sound good on stage, don’t just go on autopilot and accept that fate. Work towards finding a balance between the inadequate physical space of the venue, and the amount of perceived “space” in the music. Space has its own vibe. Space is beautiful.